Mistletoebird

Dicaeum hirundinaceum

The mistletoebird of Australia and Indonesia specializes in feeding on mistletoe berries — digesting the flesh and depositing the sticky seeds onto branches in neat lines, where they quickly germinate and grow. The bird is nomadic, in near-constant search of mistletoe berries.

Under the Mistletoe

Mistletoe is an odd plant. The name refers to more than a thousand species found the world over, all united by a penchant for parasitism. Yes, the Christmas 'kissing plant' mooches off other plants to survive.¹ It uses a specialized structure called a haustorium — what would typically be the roots in a regular plant — to penetrate the bark of trees and shrubs, squeezing its way towards the host's xylem from which it leeches water and nutrients. Most mistletoe species grow in dense clumps of twisting branches and evergreen leaves, eventually sprouting berries that dangle like sweet ornaments of snowy white or festive red.

These berries harbour the seeds of new mistletoe plants, but for them to germinate, they have to find purchase on the branch of a host plant — preferably far away from their parent bush. Some species, like the dwarf mistletoe, simply blast their seeds into the air; a build-up of water pressure in their berries causes a catapulting explosion and a 6-metre (20-foot) hail-mary flight for the seeds inside. But most mistletoes rely on intermediaries to disperse their seeds; making their berries irresistible treats for many a bird, especially in the cold of winter. And no bird likes mistletoe berries more than the mistletoebird.

Delivering Cheer (& Parasites)

Christmas in Australia is a time of sunshine and beaches, falling as it does near the peak of Austral summer, but that doesn't mean the Great Southern Land isn't festive; houses are decorated with wreaths and bunches of the flowery pink 'Christmas Bush', families gather to exchange gifts, there are Christmas day feasts with roast turkey and fruity pavlova, and trees all across the country hang laden with mistletoe berries. Around 90 species of mistletoe grow throughout Australia — 21 of which are known to be eaten and dispersed by the mistletoebird.²

An elfin critter, barely 10 centimetres (4 in) tall, the mistletoebird is a tiny nomad in near-constant search of mistletoe berries.³ It travels in erratic flutters through tree canopies as if on a sugar-high, flashing its short tail and twittering a high-pitched song (“dzee"), or mimicking the songs of other birds. It can be spotted either alone or as part of a pair. The female mistletoebird looks dusted in a grey coating of ash, with a white breast and pale red beneath her tail. The male is less subdued; glossy blue-black feathers create a cowl over his face, draping his back, wings and tail feathers, like a dark cape. His front — patterned in an alternating red-white-red — is marked with a single streak of black, like a finger smudge of charcoal.

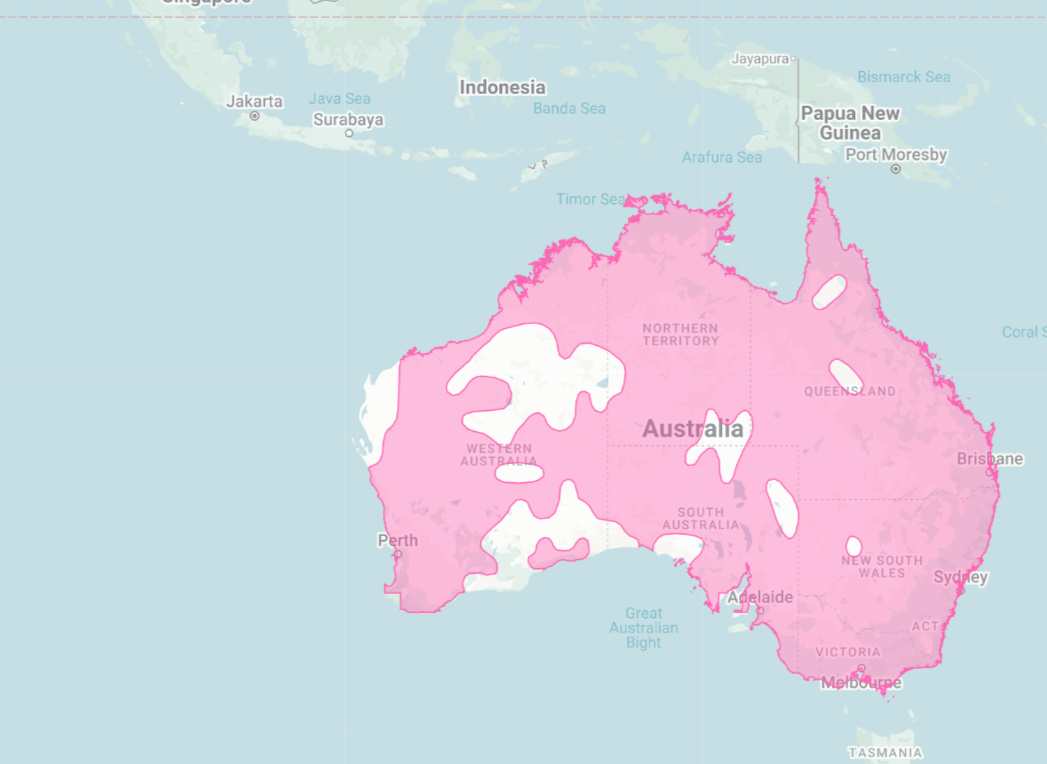

The mistletoebird is found across mainland Australia, as well as the eastern Maluku Islands of Indonesia to the north, and it goes wherever mistletoe grows. With its small, shiny beak, this bird plucks a berry and swallows it whole. Unlike most aves, this mistletoe eater lacks a muscular gizzard — the part of the stomach that grinds up food — so upon being swallowed, a berry bypasses its stomach (where a modified sphincter muscle closes shut to prevent the berry from mixing with corrosive digestive enzymes) and enters its small intestine whereupon the soft flesh is digested, but the seed is left intact to be "deposited" onto a branch. The sticky seed clings to the branch of its soon-to-be host, then swiftly germinates and infiltrates the bark with its parasitic tendrils. The next seed is deposited a few millimetres away, and so on in a line down the branch, as if the mistletoebird is sowing a row of crops — in contrast, the less specialised spiny-cheeked honeyeater deposits mistletoe seeds haphazardly, with most falling uselessly to the ground below. The mistletoebird flies from tree to tree, eating seed after seed, passing them through its simple digestive system, and delivering them onto tree branches like unwanted presents.

A Productive Parasite

Mistletoe is clearly bad for a host tree or shrub, it is a parasite after all (or at least a hemiparasite, since mistletoe can make some of its own energy via photosynthesis). It saps its host's resources, and while it usually doesn't drain its life, doesn't kill it outright — since the mistletoe relies on its host for its own survival — it can weaken the host, stunting its growth, killing off limbs, and preventing the host from containing decay, as well as making it vulnerable to diseases and other parasites such as bark beetles.

But the mistletoe isn't solely a selfish Grinch of a plant. It possesses, if not a big kind heart, at least a few benefits for its community. For one, mistletoe provides food for birds, and not only the mistletoebird; in Australia 33 bird species have been recorded feeding on mistletoe berries, 41 species feed on its flowers, while others, like the critically endangered regent honeyeater, dine on its nectar and nutritious leaves. The succulent leaves are also a favourite for many arthropods — from beetles and spiders to the caterpillars of moths and butterflies (over 25 species) — as well as significantly larger (and furrier) animals like possums and gliders.⁴

In addition to providing chow, the dense and twisted tangles of mistletoe clumps offer shade and shelter for the 245 Australian bird species known to nest within them. And even the mistletoe's destructive nature has an upside. Tree branches heavily laden with mistletoe often break and fall during stormy weather. On the ground, the leaves decay to create nutrient-rich leaf litter, while up in the tree, the break sites can develop into hollows that house insect-eating microbats or cavity-nesting birds.

The presence of mistletoe in an area bolsters the richness of wildlife — from vulnerable bird species like the painted honeyeater, to pest-controlling bats, and adorable marsupial gliders — so while it is a parasite, it is, at the same time, a provider. And none of its relationships are as remarkable as its partnership with the mistletoebird. The two organisms — plant and bird — are joined in a committed lockstep dance, a dance of inseparable symbiotic interdependence; the bird relies on the plant's berries to survive and the plant relies on the bird's unique behaviour and physiology to spread and thrive. As long as the mistletoe is around, the mistletoebird will have food to eat, and as long as the mistletoebird is around, the mistletoe will have a dedicated little helper to deliver its sticky seeds.

¹ Mistletoe has long had a symbolic role in various cultures throughout history. In Ancient Greece, mistletoe featured in the myth of Aeneas, wherein he carried the plant (the "Golden Bough") on his journey to the underworld as a safeguard. It was also seen as a symbol of male fertility (with its white berries known as "oak sperm"). From Ancient Rome to Austria to Celtic druids and the Ainu of Japan, mistletoe's association with fertility (and not only male) was and is widespread — the evergreen mistletoe bushels remain vibrant (fertile) even as their host trees lost their leaves in winter. The plant was carried and eaten by women who wanted to conceive, hidden in the bedrooms of hopeful couples, and used in "pregnancy potions".

In the Norse myth of Baldur, the mistletoe plays a ruinous role, as the near-indestructible Baldur is slain by an arrow of mistletoe thrown by his blind brother Höd (who was tricked by Loki). The tears of Baldur's mother, Frigga, are said to be the mistletoe's berries. This tale of wanton death became the basis for a custom of calling a truce between enemies if they found themselves beneath a mistletoe.

In ancient Rome, the mistletoe symbolised peace, understanding, and love. It was hung on doorways during their yearly Saturnalia celebrations — a festival in honour of the god Saturn celebrated on the 17th of December and the source of many of our modern Christmas traditions (including wreaths, candles, feasting and gift-giving).

Whether stemming from the widespread association with fertility, the Norse idea of a truce beneath the mistletoe, or the Roman presence of mistletoe during holidays, the modern Christmas tradition of kissing beneath the mistletoe became an established one in England among the servant class by the 18th century — a tradition which claimed that a kiss beneath the mistletoe would see a couple wed and any spousal quarrelling quenched.

² With mistletoe making up some 85% of its diet, few birds are as picky (specialized) eaters as the mistletoebird.

Some carnivorous birds are known to have favourite prey items. Serpent and snake eagles, as per their names, most often hunt snakes (among other reptiles like lizards, and occasionally some mammals). Several birds are particularly fond of snails. The openbill storks (one species from Africa and one from Asia) specialize in extracting snails from shells with their curved lower mandibles. While, in the Americas, both the aptly named snail kite and a wading bird known as the limpkin eat almost nothing but freshwater apple snails (genus Pomacea). The bearded vulture doesn't specialize in a particular type of prey but, rather, the state in which that prey is consumed; a very dead, skeletal state, as bones make up 85-90% of the vulture's diet.

In stark vulturine contrast, the palm-nut vulture is a staunch vegetarian, with some 70% of its diet consisting of plant matter — mostly palm nut fruits. Pesquet's parrot, a gothic-looking bird from the mountains of New Guinea, is very fond of figs; so fond that it almost exclusively subsists on a diet of a few species of strangler fig. Over on Hawai‘i's slopes of Mauna Kea, lives an endemic honeycreeper known as the palila. This small ashen-yellow bird is a seed specialist, practically eating nothing but the unripe (and toxic) seeds of the Hawai'i endemic māmane tree. The mistletoebird isn't alone in its picky preferences.

³ The mistletoebird temporarily halts its obsessive travels after mistletoe during its breeding season (August to April), when it settles down to build a pear-like nest that hangs suspended from a twig, built from plant down, wool, and spiderwebs — or at least the female builds it (the male doesn't help, nor does he help incubate the young, but he does help to provide food, which is better than nothing I guess).

To compensate for a protein-poor diet, a mother mistletoebird has to gorge on berries in order to produce her clutch of 3 - 4 white eggs. Upon hatching, the chicks are fed predominantly insects and larvae, so that they grow big (relatively) and strong, and are ready to continue the mistletoe-farming business by the time they've fledged.

⁴ It's not just wild animals that benefit from the bounties of mistletoe, people do as well. To the Indigenous people of mainland Australia, mistletoe berries are a sweet snack — known as "snotty gobble" — and are used to make a sweet drink. Both the berries and leaves were also used as medicines that treated anything from colds and sores to menstrual cramps.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Wherever mistletoe grows.

📍 Most of Australia (absent from Tasmania) and also the eastern Maluku Islands of Indonesia.

‘Least Concern’ as of 15 January, 2024.

-

Size // Small

Wingspan // 17 cm (6.7 in)

Length // 9 - 10 cm (3.5 - 3.9 in)

Weight // 9 grams (0.3 oz)

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Social 👥

Lifespan: Up to 9.7 years (in the wild)

Diet: Primarily Herbivorous

Favorite Food: Mistletoe berries 🍒

-

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Dicaeidae

Genus: Dicaeum

Species: D. hirundinaceum

-

The digestive system of a mistletoebird is relatively simple — it lacks a muscular gizzard (the part of a bird's stomach that grinds up food) and a berry passes through its system without contacting the stomach's corrosive digestive enzymes. The seed pops out intact, encased within sticky goop.

Up to 85% of a mistletoebird's diet can consist of mistletoe berries, making it among the most specialized of any bird in terms of its diet (i.e. it's a very picky eater).

Its defecating etiquette could almost be called elegant. Compare the specialized mistletoebird to another, more casual, mistletoe enjoyer — like the spiny-cheeked honeyeater, who haphazardly poops out digested seeds, most of which fall to the ground. Meanwhile, the mistletoebird deposits mistletoe seeds in a neat line along a branch so they can infiltrate their host tree.

The mistletoebird ranges across mainland Australia and the eastern Maluku Islands of Indonesia to the north. It goes wherever mistletoe grows. Of the around 90 species of mistletoe in Australia, the mistletoebird is known to eat and disperse at least 21 of them.

The mistletoebird is an elfin ave, barely 10 centimetres (4 in) tall. The female is ashy grey with a light-red undertail, while the male is glossy blue-black from his head and down his back, red and white on his front, with a charcoal line down his belly.

The mistletoebird is a nomad for most of the year, following the most abundant blooms of mistletoe. Only during its breeding season (August to April) does it settle down to build a suspended, pear-shaped nest and raise 3 to 4 chicks. After an initial diet of insects and larvae, the chicks soon transition to a predominantly mistletoe-berry diet.

Delivered onto a branch by a mistletoe bird, a mistletoe seed soon germinates and uses a structure called a haustorium (equivalent to a stem or root) to penetrate into the bark of the host tree or shrub, squeezing its way towards the xylem from which it leeches water and nutrients. The Christmas kissing plant is a mooching parasite.

Mistletoe is a plant parasite that weakens, but usually doesn't outright kill its host. All in all, it does more to help than harm its ecosystem. In Australia, mistletoe berries are known to feed 33 species of birds, while the flowers feed at least 41 species, and the leaves feed countless species of invertebrates, as well as mammals like possums and gliders. As many as 245 Australian bird species are known to nest within mistletoe.

-

Australian National Botanic Gardens

Human Ageing Genomic Resources (AnAge)

NSW Government - mistletoe myths

Backyard Buddies - mistletoe in Australia

Botanic Gardens of Sydney - mistletoe

Smithsonian Magazine - biology of mistletoe

Smithsonian Magazine - mistletoe facts

Plantlife - mistletoe

Wisconsin Horticulture: Division of Extension - mistletoe

Texas A&M Forest Service - mistletoe

Australian Government: Study Australia - Christmas in Australia

WhyChristmas?com - Christmas in Australia

Animal Diversity Web - Asian openbill

Oiseaux-Birds - African openbill

Cornell Lab: All About Birds - snail kite

Cornell Lab: All About Birds - limpkin

Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF) - bearded vulture

Curious Species - palm-nut vulture

ABC Birds - palila

Australian National Botanic Gardens - mistletoe in myth and folklore culture

Cool Green Science (The Nature Conservancy) - mistletoe: natural and human history

Fort Worth Botanic Garden - mythology and history of mistletoe

History - Saturnalia

-

Cover Photo (James Peake / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #01 (Ark Wildlife and Ollie Spacey / Tree Talk)

Text Photo #02 (Colin Wright / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #03 (helenmeldale / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #04 (Chris Tzaros / CSIRO Publishing)

Text Photo #05 (Terence Alexander / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #06 (Album / Science Source / New York Public Library, Chroma Collection / Alamy Stock Photo, Heritage Images / Colaborador, and Library of Congress)

Text Photo #07 (Ashish Inamdar / Solent News / Shutterstock, Frank McClintock / Shutterstock, Mario Böni / Stiftung Pro Bartgeier, RJ Wiley / Audubon Florida, Christ Butler / South Coast Sun, Petr Hamerník, Prague Zoo, and Aaron Maizlish / ABC Birds / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #08 (David White / iNaturalist)

Slide Photo #01 (Claire Watson / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #02 (Todd Burrows / Macaulay Library)

Slide Photo #03 (Ian Shaw / iNaturalist)