Night Parrot

Pezoporus occidentalis

The night parrot was believed to be extinct for almost 80 years. Despite widespread sightings throughout mainland Australia, this nocturnal parrot is one of the country's most elusive birds. It lives in isolated arid regions, spending most of its time on the ground and hiding within spinifex grass.

A Most Elusive Ave

Australia is home to around 850 species of different birds — from ubiquitous galahs and silver gulls to more secretive grasswrens and painted buttonquail. But, perhaps the most elusive of all the Australian aves is the night parrot. The first known specimen was collected in 1845, and, in the following decades, sparse sightings of this odd parrot were reported throughout mainland Australia. They described a small and stocky parrot, measuring no longer than 25 cm (9.8 in). Its feathers were brilliantly green, with dark markings along its back and wings, and a bright yellow underbelly. Its calls were a little ‘ding-ding’ and a short froggy ‘grieet’. However, by the early 1900s, sightings had almost completely ceased, and the parrots were silent; the last specimen was collected in Western Australia in 1912, and the night parrot was considered extinct.

But Australia isn't a country content with letting its species go. In the 1960s and 70s, a few unconfirmed sightings began to trickle in. Then, in 1979, a team from the South Australian Museum reported spotting a flock of these supposedly extinct birds. Slippery and reclusive, these parrots were like feathered counterparts to the extinct, but still sought-after thylacine from Tasmania — except the parrots eventually proved to still be around. The first substantial evidence turned up in grim fashion; dead bodies, the first found in 1990, the next in 2006. Then, after a concerted effort, scientists discovered a living population in 2013 — some 10 to 20 parrots in western Queensland. Two years later, the first live night parrot was tagged.

Nocturnal Desert Parrot

Why has this parrot been so difficult to find — so difficult that we thought the species extinct for nearly a century? Part of the answer is in the name. Out of the 400 or so parrot species around the world, only two are nocturnal. One is the flightless kākāpō of New Zealand and the other is this appropriately named night parrot. Unlike its Kiwi cousin, the night parrot can fly — making low, short flights — but it doesn't seem much inclined to. Usually, it stays on the ground, quickly dashing from one spinifex tussock to the next. That leads us to another part of the answer; the night parrots shy habits and secluded habitat.

Most of Australia's wildlife (and human life) is found around its coasts. Only the hardiest of animals call the interior of Australia, the vast and arid Outback, home. If it wasn't for the patches of spinifex grass and the occasional hardy eucalypt — a ghost gum or desert bloodwood — this landscape would resemble a Martian wasteland; burning ochre, beautiful but barren. It is here, in these shrublands, that the night parrot is believed to live; running across the dry earth, sheltering in tunnels of spinifex grass, and emerging at night to forage for seeds. Is it so surprising then that a small bird, which lives in the inhospitable interior where few people venture, and hides in the shrubbery, only coming out at night, is so seldom seen?

Cryptic and Critically Endangered

The final explanation for the night parrot's rarity is just that; it is rare, its populations are low, and it seems they're only decreasing. The species is currently considered 'critically endangered' — the most dire conservation assessment, only followed by 'extinct in the wild' and simply 'extinct'. The problem is that this parrot is so rare, that we don't know enough about it yet to determine which threats are the most critical, which threats must be tackled first.

Fires are a danger to both the wildlife and people of Australia. Between the years of 2016-17 and 2020-21, around 35% of Australia’s total forest area burned, and an estimated 3 billion animals were impacted in the catastrophic 2019-20 bushfires alone. Much of Australia's tree flora is essentially fire-kindling; comprised of eucalypts — with highly flammable bark and oils, and adapted to drop their seeds when burned — and dry bushland grasses — such as the spinifex that the night parrot relies on for shelter and nesting. The night parrot literally lives inside the world's most flammable home in a landscape prone to quick-spreading wildfires (especially during droughts). One stray spark or unlucky lightning strike and a single flame can jump from spinifex tussock to eucalyptus tree, decimating a landscape, displacing wildlife fast enough to flee, and scorching those that aren't.

The threat of wildfire to the night parrot is more serious in some areas than others. Northeast of Western Australia stretches the Great Sandy Desert. This vast stretch of aridity is dominated by sand dunes and sandstone mesas, but it's more than just sands; some 92% of its area is covered by spinifex grass, acacia shrubs, and scattered eucalypt trees. It is ideal night parrot habitat — practically untouched by any human industry — but it's also especially vulnerable to fires sparked by lightning strikes.

In other parts of Australia, different threats bare their teeth. Using camera traps and scat analyses, researchers determined the most common predators that prowl night parrot roosting areas; dingoes. However, rather than parrot hunters, these Australian canids appear to be unwitting guardians of the parrot. Based on information from other areas (likely areas closer to human habitation), researchers suspect that invasive feral cats are the major predatory danger — as they are to native birds the world over. Often feasting on these feral felines, and simply keeping them at bay with their doggy presence, the dingoes keep cat populations down and the night parrots safe.

Other invasives pose a less savage, but potentially just as serious, threat. Grazing by livestock like cattle and sheep, or introduced herbivores like rabbits and camels, can degrade night parrot habitat, while introduced plants, such as the highly flammable buffel grass, only increase the already-high risk of intense wildfires. And, of course, anthropogenic climate change also rears its ugly head; causing prolonged dry periods, more intense heatwaves, and unpredictable, thundering, flashing, fire-starting weather.

Parrot Party

Throughout this parrot's known history, only a few scattered populations, each of just 10 or so individuals, have been found across Queensland and Western Australia. That changed in 2024. Within the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area, part of the Great Sandy Desert, a team of Indigenous rangers and scientists discovered the largest ever known population of night parrots. By surveying occupied roosting sites, they estimated that some 40-50 parrots might be present in the protected area — a relatively small number for most populations, but a veritable party by night parrot standards.

The key to protecting the parrots lies in learning more about them, and with increased public attention — sparked by this recent discovery, and simply by the parrot's cuteness and cryptic nature — there's also been increased interest to study and save the species.

The Ngururrpa researchers aim to learn more about the parrot by using cameras, songmeters, and DNA testing kits, while still maintaining the protected areas isolation — minimal people and vehicles, no weeds or livestock. The Government of Queensland has already created a reserve where livestock grazing, timber collection, and mining aren't permitted; protecting large a swathe of wilderness, including night parrot habitat. A programme to target feral cats in Diamantina National Park (in South West Queensland) began in 2023. Bush Heritage Australia (BHA) works to conduct surveys across the country and manage known threats to the parrot. While CSIRO has already sequenced the genome of the species. And, if you're interested in updates about the parrot, or want to get involved, you can keep up with the Leading Night Parrot Conservation here!

As with any endangered species, the more we learn about this cryptic parrot, the better we get at protecting it. The largest known population of night parrots had remained hidden until 2024 — hopefully, there are more little green parrots, hiding out in the desert darkness and sprinting among the spinifex, than we know.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Arid and semi-arid areas with spinifex grass.

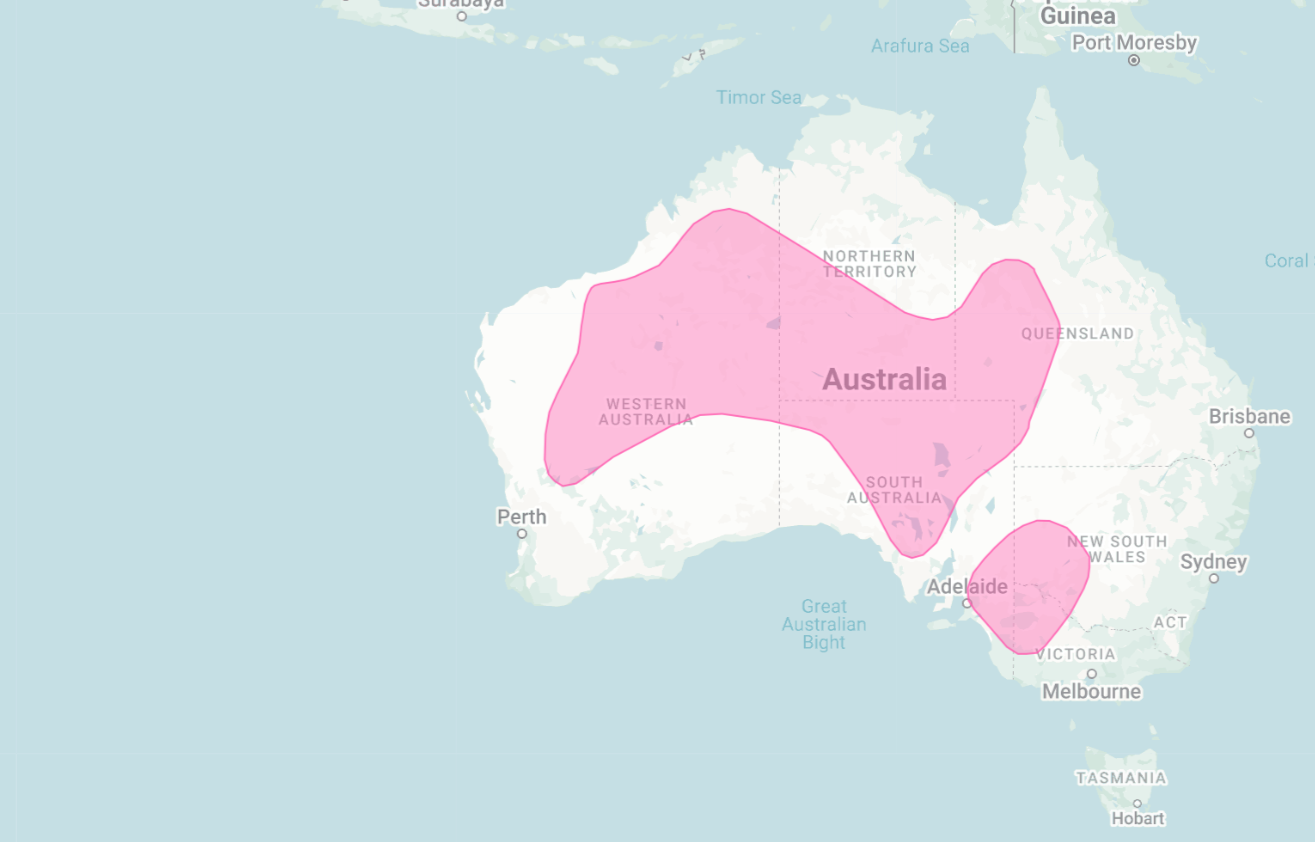

📍 Across Australia’s interior; from Western Australia to W Queensland and NW New South Wales

‘Critically Endangered’ as of 09 December, 2021.

-

Size // Small

Wingspan // 44 - 46 cm (17.3 - 18.1 in)

Length // 22 - 25 cm (8.7 - 9.8 in)

Weight // Around 100 grams (3.5 oz)

-

Activity: Nocturnal 🌙

Lifestyle: Social 👥

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Herbivore

Favorite Food: Seeds and grasses 🌱

-

Class: Aves

Order: Psittaciformes

Family: Psittaculidae

Genus: Pezoporus

Species: P. occidentalis

-

The night parrot lives across Australia's arid interior; from Western Australia to Western Queensland and Northwestern New South Wales.

Out of the 400 or so parrot species around the world, the night parrot is one of only two nocturnal parrots — the other being the flightless kākāpō of New Zealand.

The night parrot shelters in tunnels of spinifex grass during the day, coming out at night to feed on seeds, grasses, and grains.

This parrot typically moves along the ground and although it can fly, it doesn't do so often and usually only for short distances.

The call of a night parrot is a little ‘ding-ding’ and a short froggy ‘grieet’.

The first known night parrot specimen was collected in 1845. Several decades of sparse sightings followed but, by the early 1900s, sightings had nearly ceased. The last specimen was collected in 1912 and soon after the species was presumed to be extinct.

Like a feathered thylacine, people continued to search for this "extinct" parrot and several sightings were reported in the 60s and 70s. Then a dead parrot was found in 1990 and 2006. And, finally, in 2013, scientists discovered a living population.

The species is considered 'critically endangered' with major threats including wildfires, invasive predators (feral cats and foxes), and overgrazing by cattle causing habitat degradation.

Dingoes were the most commonly recorded animal around known night parrot nesting sights — but instead of preying on parrots, the dingoes actually keep away feral cats.

The best estimate for how many mature parrots live in the wilds is only 200 individuals, but given how elusive the species is — emerging at night and living in the inhospitable Outback — it is a rough estimate.

In 2024, in part of the Great Sandy Desert, a team of Indigenous rangers and scientists discovered the largest ever population of these parrots; some 40 to 50 individuals, based on the prevalence of nesting sights.

-

Australian Government: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry - forest fire data

WWF - Australian bushfires

NSW Government - climate change impacts on bushfires

Encyclopedia Britannica - Great Sandy Desert

The Gibson, Great Sandy, and Little Sandy Deserts of Australia by Eddie John Van Etten

-

Cover Photo (Bush Heritage Australia)

Text Photo #01 (Elizabeth Gould / Wikimedia Commons)

Text Photo #02 (Nick Leseberg / The Canberra Times)

Text Photot #03 (Adam Dederer / WWF-Aus)

Text Photo #04 (Nigel Jackett / Macaulay Library)

Text Photo #05 (ABC News / Flinders University)

Slide Photo #01 (John Young / Audubon)

Slide Photo #02 (Steve Murphy / Threatened Species Recovery Hub)