Common Cockchafer

Melolontha melolontha

The common cockchafer spends its first 3 to 5 years below ground, growing as a larva. Then, all at once, these beetles emerge as adults in great numbers during spring. They clumsily buzz about, using their frilly antennae to find mates and reproduce — they live for only 6 weeks in this form.

Charasmatic Cockchafer

The common cockchafer is a charming and familiar beetle, found throughout much of Europe and parts of western Asia. At about 3 cm (1.2 in) long, it's quite a bulky beetle. Its body is black and fuzzy, covered by brown wingcases and carried on six brown legs. Its big inky compound eyes have 5,475 facets each, providing the cockchafer with sharp vision — and extra cuteness. Two fan-like antennae sprout from its head, and these stylish appendages are more than ornamental. The antennae are chemoreceptors, able to sense chemical compounds floating in the air — essentially smelling — and their flat leaf-like segments increase the surface area with which they catch those compounds.¹ Curiously, you can also use a cockchafer's antennae to figure out its sex; females have six "feathers" on each antenna, while males have seven.

A common cockchafer uses its fan-like antennae to find mates.

Beetle Uprisings

You might well live in the midst of thriving cockchafer territory, and not see a single beetle for up to five years. This is because they remain below ground as larvae, feasting and growing, for the first three to five years of their lives. But once the beetles do finally make their appearance, they are unmissable. They emerge from the below ground almost in unison during spring. Their newly formed wingcases are dusted with white powder. For the first time in their lives, they take to the skies, and their flight is decidedly awkward. They buzz about loudly, swerving clumsily through the air, colliding with outdoor lamps and window panes. Their antennae are indispensable now, as each beetle must sense and follow the pheromones of a willing mate — and they must do so quickly, for they only live for six weeks as adult beetles.

In some areas, these chitinous hordes rise up like great beetle plagues, almost biblical in scale — an apt parallel, given their place in the scarab beetle family.² In 1574, one such emergence in the Severn Valley of England was so grand that beetle carcasses prevented watermills from turning. But outside of such extreme cases, adult beetles are little more than a bumbling, buzzing annoyance to humans. Swarms of cockchafers feast on flowers and tree leaves, but rarely to a destructive level. Individually, each cockchafer beetle is large and loud, but completely harmless. It has no mandibles big enough to bite. The end of a female cockchafer's abdomen does curve into an intimidatingly sharp point. But this is not a stinger, it's a pygidium — used not to puncture skin, but to place eggs beneath the soil, with each female beetle laying up to 80 eggs.

Subterranean Terrors

A common cockchafer larvae.

No, it isn't the beetles one should worry about, but their larvae. The subterranean young have none of the charm of the adult beetles. Their bodies are pale and plump, like bloated worms, and their rears are translucent, bulging black. They often lay buried with their bodies folded in a C-shape — like grotesque fetuses in a womb of dirt. They drag themselves through their lightless world using six hairy limbs. These are located near orange, alien-like heads, equipped with gnawing mandibles.

Their appetites are voracious; their lives are a cycle of gorging and growing. They are the nightmare of gardeners and farmers, as grubs only eat living vegetation. They crowd around roots to chew and devour them, slowly sapping life from the plants above. Their feasting often goes unnoticed until the damage is severe — able to ravage entire fields, leaving behind only sickly yellow, withering plants. The grubs grow fat and large, and by the time they begin to pupate, they may be as large as 4 cm (1.6 in), longer even than the adult beetles they will become.

Humans Vs. Beetles

A common cockchafer in flight.

Such is their destructive power that in 1320, in the Avignon commune of France, the entire cockchafer species was taken to court. How this was done can be comedic to imagine — did they have a cockchafer representative present in the room? Regardless, the ruling was decisive; the cockchafers were outlawed and ordered to leave town upon pain of death. Needless to say, the beetles likely didn't heed human laws and many were undoubtedly killed. In modern times, beetle persecution has become a lot more efficient. In 1911, more than 20 million individual beetles were collected in 18km² of forest, in an attempt to prevent the spawning of the next generation. Pesticides now do the work of killing many beetles and their grub — often working too well — however, more strict regulations are being put in place to prevent the complete disruption of ecosystems and damage to the environment.

It seems that, for millennia, cockchafers have been eating our crops and we have been tormenting them in return. There are records from Ancient Greece of young boys tying threads to cockchafers, tethering them down, and watching them fly aimlessly in circles — children from Victorian England did the same by way of a pin through the wing. In various places and at various times, both beetle and grub were eaten as a snack or delicacy — there exist French recipes from the 19th century for making cockchafer soup and newspaper stories from 1920s Germany of children munching on sugar-coated cockchafers.

It may seem that the cockchafer's name is just another jab at this beetle, but despite its suspect implications "cockchafer" isn't actually an insult. Its origins have nothing to do with phallic abrasions. In this this context, "cock", derived from an old definition of the word, means "big", and "chafer" is just a name for a type of beetle. So "cock-chafer" essentially just means "big beetle" — nothing insulting or improper about it. Another name for this beetle — perhaps a more well-known one — is "May bug", as that is the month when these beetles most often emerge to buzz through the air after their years of growing below ground as destructive little monstrosities. It almost seems as if each locality in the UK has its own name for the cockchafer, a few include; the chovy, mitchamador, kittywitch and midsummer dor. The doodlebug is another — one that was later used during WW2 as a nickname for the German's V-1 flying bomb planes, as the planes produced a buzzing much like that of the beetle's.

¹ Antennae are the primary olfactory organs of insects, whereas we humans (and most mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians) rely on olfactory receptors within our nasal cavities to identify the chemical makeup of the air. All insects — and there are a lot of them, more than a million known/named species and an estimated 5.5 million in total — have antennae, from beetles, bees and butterflies, to termites, fleas, and mosquitoes. Spiders and scorpions, as they are not insects but arachnids, have no antennae.

The three basic parts of an insect antenna; the scape, pedicel, and flagellomeres.

Three basic parts make up an insect antenna. The segment at the base is the scape, which is attached to the head inside a socket that enables the insect to manoeuvre the antenna. Next is the pedicel, a segment with muscular connections that allows for finer antenna control. The last, and usually longest, segment is the flagellum, which is made up of smaller segments called flagellomeres that contain many sensory cells. It is this last segment that the cockchafer modifies into a fan-like structure.

The sensory cells along the flagellomeres are called olfactory sensilla. Although they detect odour much like the cells in our noses — a floating molecule makes contact with a cell specialised to recognise its particular odour and the cell sends an electrical signal to the brain — the insect's sensilla are much more sensitive, able to detect odours at much smaller concentrations. The fact that antennae are paired and manoeuvrable also enables an insect to more accurately pinpoint the source of an odour, doing so by comparing the minuscule difference of odour concentration between the two antennae.

Many beetles, like the cockchafer, have antennae that terminate in extravagant-looking fans and frills. Glowworm beetles flaunt large feathery antennae, as if about to perform at a cabaret. The antennae of the feather-horned beetle are even more impressive, almost hypnotizing. Longhorn beetles have whip-like antennae that exceed the length of their entire bodies. The black and amber burying beetle has small orange-tufted antennae that specialise in locating decaying matter. While male and female dung beetles use their sensitive combed antennae to detect the scent of faecal odours, so that they can meet up for a romantic date near a dung pile.

An illustration of a few scarab beetles — there are around 35,000 species.

² The scarab beetles are a large family (Scarabaeidae) with some 35,000 species. Found the world over, scarab beetles are typically heavy and oval-shaped, with club or fan-like antennae and front legs adapted for digging. In size they range from the most minuscule of beetles — Termitotrox cupido, a 1.2 mm (0.047 in), blind, and flightless scarab that lives in termite nests — to the world's heaviest — the goliath beetle, which can weigh almost 60 grams (2.1 oz) as an adult and up to 100 grams (3.5 oz) as a larva — to the worlds longest — the Hercules beetle, which, with its exceptional horn, can grow to be 17 cm (6.8 in) long. The scarab beetle famously had a special place in the culture of Ancient Egypt. The particular species that was revered is now known as the sacred scarab (Scarabaeus sacer) and is actually a type of dung beetle. It was the symbol of the scarab-faced god Khepri and its recognizable form can be seen in Ancient Egyptian amulets and carved into various stone structures.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ A wide range of habitats but prefer fields, meadows and grassland.

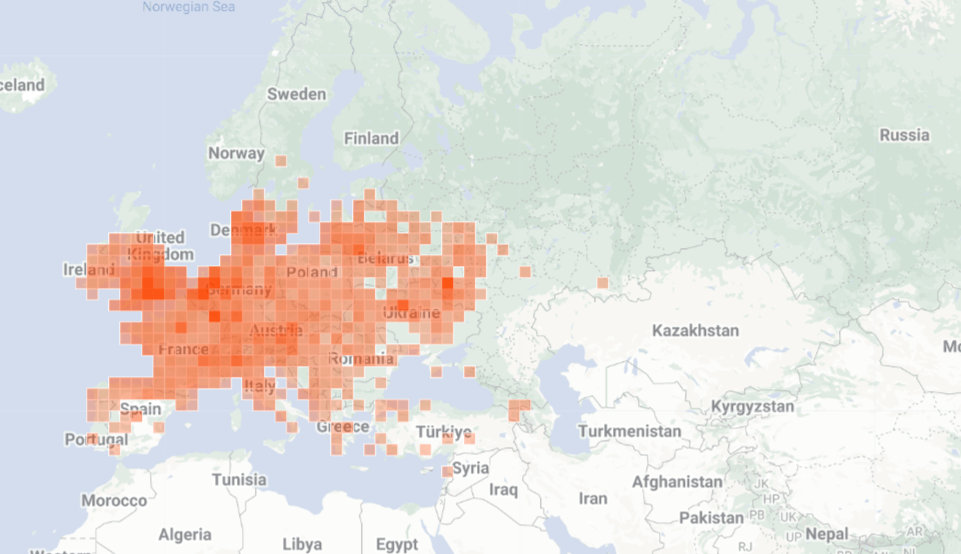

📍 Across most of Europe and parts of western Asia.

-

Size // Tiny

Length // 2 to 3 cm long (1 - 1.2 in)

Weight // 0.4 to 0.9 grams (0.01 - 0.03 oz)

-

Activity: Crepuscular or Nocturnal 🌙

Lifestyle: Social 👥

Lifespan: 3 - 4 years as larvae & abouts six weeks as adult beetles.

Diet: Herbivore

Favorite Food: Plant roots as larvae, grasses and leaves as adults. 🌱

-

Class: Insecta

Order: Coleoptera

Family: Scarabaeidae

Genus: Melolontha

Species: M. melolontha

-

The name "cockchafer" is composed of "cock", which used to mean "big", and "chafer", which is the name for a type of beetle — ultimately just meaning "big beetle".

Other names include May bug/beetle and June bug/beetle, in reference to when it typically emerges from the soil as an adult. Nicknames from the UK include chovy, mitchamador, kittywitch, midsummer dor, and doodlebug.

In the year 1574, in the Severn Valley of England, there occurred an emergence of beetles so grand that their carcasses prevented watermills in the area from turning.

The common cockchafer is harmless to humans — the worst it will do is clumsily fly into you or annoy you with its buzzing. Females sport sharp-looking decurved appendages on their abdomens (called pygidia), but these are just used to lay eggs beneath the soil (around 80 eggs).

The larvae of this beetle live underground and can grow larger than adult beetles — 4 cm (1.6 in) in length. They gnaw on the roots of living plants, causing mass damage to crops. In their adult form, the beetles prefer flowers and leaves, and are much less destructive.

The common cockchafer belongs to the scarab beetle family (Scarabaeidae), a group with around 35,000 species.

Both children in Ancient Greece and Victorian England enjoyed tormenting these beetles; the former by tying tether threads to their bodies and watching them fly in circles, while the latter pinned them down by the wing.

In 19th-century France, they would cook the beetles in "cockchafer soup", while in 1920s Germany, the beetles were candied and eaten as snacks.

-

How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth? by Nigel E Stork

Science Learning Hub (Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao) - Insect Antennae

Amateur Entomologists' Society - Insect Antennae

iNaturalist - Scarab Beetles (Family Scarabaeidae)

Encyclopedia Britannica - Dung Beetles

-