Japanese Badger

Meles anakuma

Endemic to Japan, the Japanese badger — like other badgers — lives in underground dens called "setts". However, the Japanese badger is known to be more solitary, with even mated pairs often living in separate setts. It is currently unknown why this is the case.

The Mujina (貉) & Anaguma (穴熊)

In Japanese folklore, there exists a shapeshifting yōkai — a type of supernatural entity or monster — called a mujina (貉). A mujina was once a regular badger who, in one way or another, developed magical abilities. It is known as a trickster, using its shape-shifting abilities to make fools out of the wicked. One form it takes is that of the nopperabō (野箆坊); walking mountain and village paths in the dark, it appears as a seemingly normal human but as it steps into view, it reveals a face with no eyes, nose, or mouth; with no features whatsoever — sending its victims running in a startled panic. But mujina are also exceedingly shy. On dark and quiet nights, when the streets are all but empty of people, a mujina shapeshifts into the form of a young boy dressed in a kimono and drifts about singing its midnight song. If it encounters a human along the way, it flees into the wild darkness of the forests and mountains, shifting back into its original animal form.

Its natural form is that of the Japanese badger; stocky and furred, weighing around 5 kg (11 lbs) and measuring some 75 cm (2.5 ft) long from its prominent porcine nose to the tip of its short tail — with a male usually larger than a female. Its snout is long and tactile, while its ears are small and round, like fluffy white cotton balls placed on either side of its head. Its fur coat is a blend of browns, greys, and blacks, and its light-furred head is marked with a pair of vertical brown stripes, one over each of its unusually small eyes. In Japan today, such an animal (the non-magical version) is called an anaguma (穴熊), which literally translates to "hole-bear". A bear it is not, but it is an avid digger of holes.

Setts

The anaguma's, or Japanese badger's, limbs are robust — covered in dark fur, as if dirtied by digging in the mud. Each of its broad feet sports five curved, non-retractable claws that it uses to excavate subterranean dens called "setts". These badger burrows consist of many interlocking tunnels leading to specialised chambers and can have over five entrances. Such communal underground shelters are continually expanded and improved, and are even known to be passed down through many generations of badgers, but a simple sett can also be nothing more than a tunnel leading down to a single sleeping chamber. Inside, the badger shelters itself from meteorological menaces — such as the biting cold of winter, during which time it hibernates, from mid-December to February — and predatory perils — such as foxes, feral dogs, humans, and, until relatively recently (declared extinct in 1905), wolves.

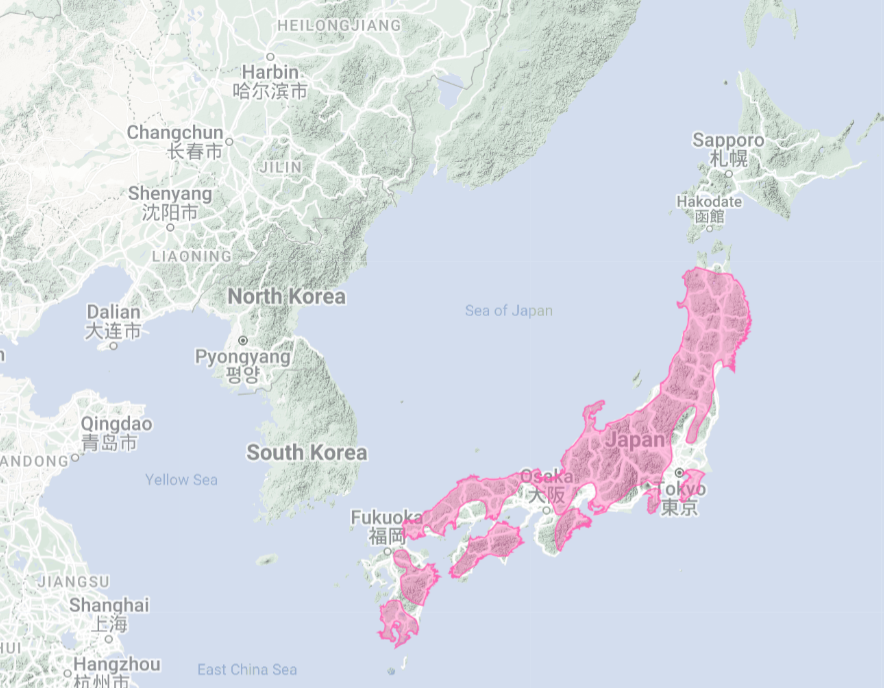

Such burrows lay hidden among the forests and grasslands, as well as cultivated and suburban areas of Japan; from northern Honshu (Japan's largest island) to Kyushu in the south. The entrances to Japanese badger setts are dug in inconspicuous and covert spots — allowing for stealthy comings and goings — usually along hills and slopes from sea level to altitudes of 1,700 metres (5,580 ft). A female badger may hold between 20 and 40 setts scattered throughout her territory, while a male can hold upwards of 70. Well-worn, meandering paths mark the badger's wanderings and large heaps of scat act as territorial signposts, while the territory boundaries are marked with scents from the badger's subcaudal gland (a.k.a. the anal gland).

The Antisocial Badger

Many Eurasian badger species prefer a communal existence — living socially in groups (called 'cetes') which share expansive setts. The Japanese badger is less socially inclined. What's the reason behind the atypically introverted behaviour of these Japanese mustelids? Currently, the answer is unknown. They must, of course, socialize in order to breed, and both males and females may do so with multiple different mates — what is known as a 'polygynandrous' mating system. A male expands his range to overlap with that of several females — but will usually refuse to share a sett with any of them — and then proceeds to court all of them; soliciting a female's attention by raising his tail straight upwards and making a deep, whinny purring noise. Foreplay, prior to coupling, can sometimes be violent and, on account of musk emission, smelly.

After copulation, the future of the couple's offspring is in the mother's paws. Pregnancy typically lasts some 49 days and since mating can take place year-round, even during winter, a birthing at the wrong time — with cold temperatures and scarce resources — could be disastrous for the mother and her children. To circumvent this issue, a mother Japanese badger employs 'delayed implantation'; a reproductive strategy in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays becoming implanted in the lining, allowing the mother to wait for favourable conditions in which to give birth and raise her pups, typically in the spring. A litter of 1 to 4 cubs is born — although larger ones of 6 are possible — and raised in the dark, but safe, world of their mother's underground den. After much maternal care, the female pups leave the den permanently at around 14 months old, while the males can mooch off their mother for as long as 26 months before they finally move out.

Like the shapeshifting mujina, the Japanese badger is a shy and secretive creature of the night. Its eyes are equipped with tapeta lucida — a layer of tissue behind the retina that increases the light available to photoreceptors — and many rod photo-receptors that function well in low light. However, for a nocturnal animal its eyes are unusually small, meaning that sight is likely less important than its other senses (in contrast to other nocturnal animals such as tarsiers and night monkeys, who possess unnervingly large eyes). The Japanese badger's sense of smell is likely its greatest talent, used to navigate a smelly social world of scent markings. For badgers that do live in social groups, the dominant member is known to scent mark each of his group members — giving each a stinky name tag. To obtain food, the badger also employs its nose; guiding it to insects and earthworms, small mammals and carrion, fruits and vegetables — anything it can opportunistically forage.

Japan’s Badger

The only badger in Japan, this endemic animal plays a unique role in the ecosystems of its archipelago home. Its digging habit turns over soil, aerating it and allowing water and nutrients to seep deeper into the ground — creating a more fertile land for plants. Like a farmer, having readied the soil, it then disperses seeds: depositing those of berries, fruits, and vegetables in its droppings. Feeding on small mammals and insects, the Japanese badger also serves as a form of pest control, ensuring that pest populations stay in check.

In turn, we humans thanked its efforts by hunting it — a practice that has thankfully been in decline since the 1970s. Unfortunately, also in decline is the Japanese badger population, for while there is less hunting, the badger is losing its habitat to agricultural developments, having to compete against crafty invaders like the North American raccoon, and is forced to cross vast highways of hurtling cars. Ways to coexist together — badger and human — are being sought. For example, tunnels are constructed to deter badgers from crossing roads and wildlife corridors allow the badger to travel through human-dominated lands. It is estimated that there are 4 adults/km² in the Tokyo suburbs and the species itself is currently listed as 'Least Concern'.

-

📍 Mount Daisen, Tottori Prefecture, Japan 📅 16 May, 2024

As mentioned above, the Japanese badger is a nocturnal, secretive, and shy creature. So when one absentmindedly waddled across the road in broad daylight, just a few metres ahead of me, it took me a few moments to process what I was looking at.

This was in the Tottori Prefecture, on the winding roads about 800 metres (2,600 ft) up Mount Daisen. Few cars passed along the road I was walking beside. Forest climbed up one side of the road and fell on the other. I didn't see the stout furry creature emerge from the ascending wall of trees, but it took no pains to hide as it leisurely crossed the road, my path, and entered the forest on the other side. It didn't so much as glance in my direction, nor turn at the snapping of my camera shutter as I fired off heedlessly at this rare creature. It milled about in the bushes for a while; I stood watching it from on high. As it was readying to take off, I coughed, like one would to discreetly get a person's attention. The badger was anything but discreet in its reaction. I had read of the badger's keen hearing, its penetrating sense of smell. I thought that it was surely aware of my presence, having done little to hide it, that maybe it was just unthreatened, unbothered. Apparently not so. It wheeled around on me as if I was a barking, lunging wolf. I got one shot of its startled stare, obscured in green foliage, before it briskly plodded off into the underbrush.

What it was doing out and about during the day, so oblivious to the world, I don't know. It was an exceptionally overcast day, so perhaps, with its poor vision, it was convinced that night had come early.

Badgers of the World

Most will be familiar with one kind of badger or another. These stout, thick-bodied creatures don't make up a single familial group — they are 'polyphyletic', in that they don't form a natural taxonomic grouping — rather, what we call badgers are spread among the mustelid family (Mustelidae; which also includes weasels, ferrets, stoats, otters, and the wolverine) and the skunk family (Mephitidae).

Americans, excepting those from the East Coast, may be familiar with the American Badger (Taxidea taxus). Comically stout and flat — almost like a furry table with a head — the American Badger, like the Japanese, is nocturnal and solitary. Its wide waddling gait may not lend it the air of a fierce predator, but in certain parts of the U.S. it's known to team up with coyotes to form extremely effective hunting partnerships where each member makes up for the other's shortcomings: the coyote uses its speed to chase prey above ground, while the badger can easily slip into burrows to catch or flush out hiding subterranean prey.

Across the pond lives the European badger (Meles meles). A sturdy-bodied digger — although a bit more streamlined than the American — the European badger is the most social of the badgers, living in communal setts of up to 23 adults. It is also one of the only hunters of hedgehogs, its thick skin shielding it from the stabbing spines and its long claws giving it extra reach. The Asian badger (Meles leucurus), you guessed it, lives throughout much of Asia; from Russia and Kazakhstan in the West to the Korean Peninsula in the East. Then there’s the famously vicious and uncaring honey badger (Mellivora capensis), also known as the ratel, which spans a multi-continent range, dominating much of Africa, southwestern Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This durable creature seems impervious to almost all attacks, including but not limited to bee stings — important for acquiring its favourite snack of bee larvae — porcupine quills, dog bites, and snake venom.

In Southeast Asia, we encounter the weirdos among badger-kind. Many of these appear to be chimeric combinations of badger and features of other animals. The three species of hog badger (genus Arctonyx) look quite badger-like in body, but their snouts end in flat and wide, pig-like noses. The six ferret-badgers (genus Melogale), are sleeker than your typical badger, but stouter than your typical ferret — a kind of midway point between the two mustelids. The charmingly named stink badgers (genus Mydaus) are just straight-up skunks (in the skunk family Mephitidae) that look somewhat like badgers. They exhibit the iconic, skunkish black-and-white coat — some look like they're sporting frosted hairdos — and possess the ability to expel a foul-smelling liquid.

Thus concludes our world tour of badgers. Inspecting a "badger world map", it looks like these species have carved up the world into their own badger kingdoms, where they fill the badger niche and let no other badger tread — one badger in America, one in Europe, one in Africa, and one in Asia (excepting the overlapping oddities in Southeast Asia). The only continents lacking in badgers are South America, Australia, and Antarctica.

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Variety of woodland and forest habitats

📍 Japan; the islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu.

‘Least Concern’ as of 03 March, 2015.

-

Size // Medium

Length // 79 cm (31 in) in males, 72 cm (28 in) in females (total average body)

Weight // 3.8 to 11 kg (8.4 - 24.3 lb)

-

Activity: Nocturnal🌙

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: 10 - 20 years

Diet: Omnivore

-

Class: Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Mustelidae

Genus: Meles

Species: M. anakuma

-

In Japanese, this badger is known as an anaguma (穴熊), which literally translates to "hole-bear".

The Japanese badger's burrow or "sett" can have over five entrances and can consist of many interlocking tunnels leading to specialised chambers — or the sett can just be a simple tunnel leading to a single sleeping chamber.

A female badger may hold between 20 and 40 setts scattered throughout her forested territory, while a male can hold upwards of 70 — each connected by pathways.

The Japanese badger marks its territory with piles of scat and a smelly scent from its subcaudal, or anal gland.

This badger typically hibernates in its den from mid-December to February.

These badgers breed year-round and the female practices "delayed implantation" — a reproductive strategy in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the lining, allowing the mother to wait for favourable conditions in which to give birth and raise her pups, typically in the spring.

A female pup leaves the den permanently at around 14 months old, while a male can stay with his mother for as long as 26 months.

Being the only badger in Japan, this species plays an important role in its ecosystems; it turns over and aerates soil as it digs, making the earth more fertile, it disperses seeds in its scat, and it keeps pest populations in check.

The Japanese badger inspired the myth of the mujina (貉), a yōkai — a type of supernatural entity — which is characterised as both a trickster and a shy being. A mujina typically looks like a regular Japanese badger, but can shapeshift to take the form of a faceless man or a young singing boy in a kimono.

-

Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

International Wolf Center - Japanese Wolves

Badgerland - Badger Setts

National Geographic - American Badger

The Wildlife Trusts - European Badger

Mammal Society - European Badger

Animal Diversity Web - Honey Badger

-

Cover Photo (Aline Horikawa / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #01 (Matthew Meyer / Yokai.com)

Text Photo #02 (Marshal Hedin & caroline legg & David Blank & Sumeet Moghe / iNaturalist)

Text Photo #03 (Charley Hesse & ihenglan & Chien Lee / iNaturalist)

Slide Photo #01 (Alpsdake / iNaturalist)